Cal U is working with the Greene County Historical Society on the project to examine bones believed to be from Native Americans.

The Greene County Historical Society is partnering with Cal U to help identify and match hundreds of uncatalogued remains, believed to be from Native Americans.

The bones —teeth, skulls and other fragments — need to be reported under terms of the Native American Graves Repatriation Act, says Matthew Cumberledge, executive director of the historical society.

The goal is to report the remains and to facilitate the process if any tribal descendants should wish to claim them for burial.

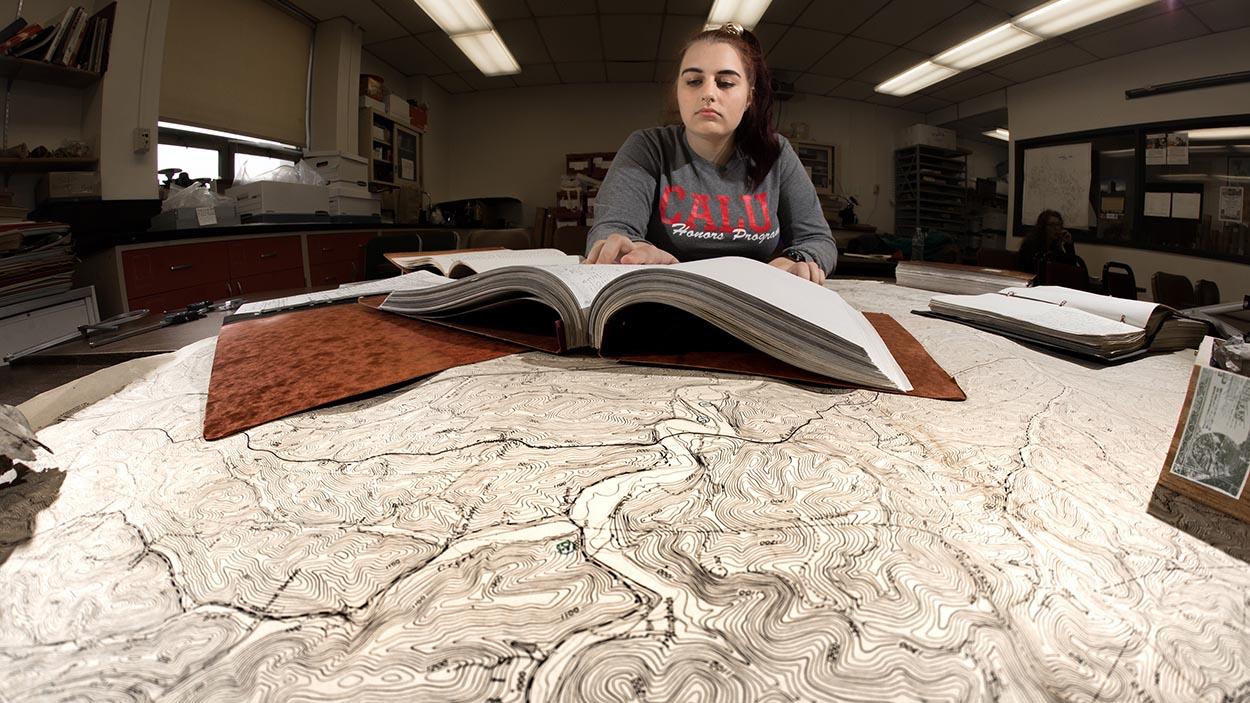

Dr. Cassandra Kuba, a professor of anthropology at Cal U, and nine students have been working throughout the fall semester on the project. The work is expected to continue through spring.

They are analyzing 700 adult teeth, 150 baby teeth, 30 skulls, not all of them complete, and other parts, including 42 mandible pieces, to verify they are Native American and match what they can.

“They are taking measurements and taking note of evidence of disease or infection or other features that might allow us to reaffiliate the remains,” Kuba says.

“The measurements of certain teeth should be consistent, and there are certain diseases that affect the health of bones that allow us to say they came from the same person. It tests (the students’) ability to determine if separate fragments really do belong together.

“The remains could represent 10 different sites or more from all sorts of time periods.”

Cumberledge says the remains were excavated in the 1930s, mostly by founding members of the historical society.

Under the Works Progress Administration, archaeologists and amateur archaeologists were paid to excavate sites,” he says.

“Unfortunately, over the last 70-plus years, the remains have been moved and repacked, and they lack context. They were all in one box, somewhat loose. One or two sets may be connected to a specific site, but the rest are not.

“Today, if you came across human remains at a site, all work would immediately cease. That was not the case then.”

Cumberledge says the historical society appreciates the collaboration.

“I’m not an anthropologist, and you don’t just look in the Yellow Pages to find someone who does this type of scientific study,” he says. “Dr. Kuba and her students have been a tremendous asset, and the enthusiasm the students have had for this project and the care with which they have treated the remains has been exceptional.”

Cearra Mihal, a senior anthropology major, has spent much of the semester in the Frich Hall lab.

“Working with co-mingled remains means having to go through and test what I’ve learned for four years,” she says. “We’ve had to decide if the differences we see in the bones are the result of pathologies or normal deviations.

“The fact that we can help (the historical society) out with this project makes me feel good. It’s a great learning opportunity for us, and it helps them solve some mysteries.”

Adds Cumberledge: “To a small degree, I feel like I’ve gotten to meet these people,” he says. “Dr. Kuba has shared what she has learned from studying the remains, and I’ve gotten a sense of who they were as people, as opposed to the bland, impersonal facts. On a human level, it’s been quite a wonderful experience.”